Learning From Rich People

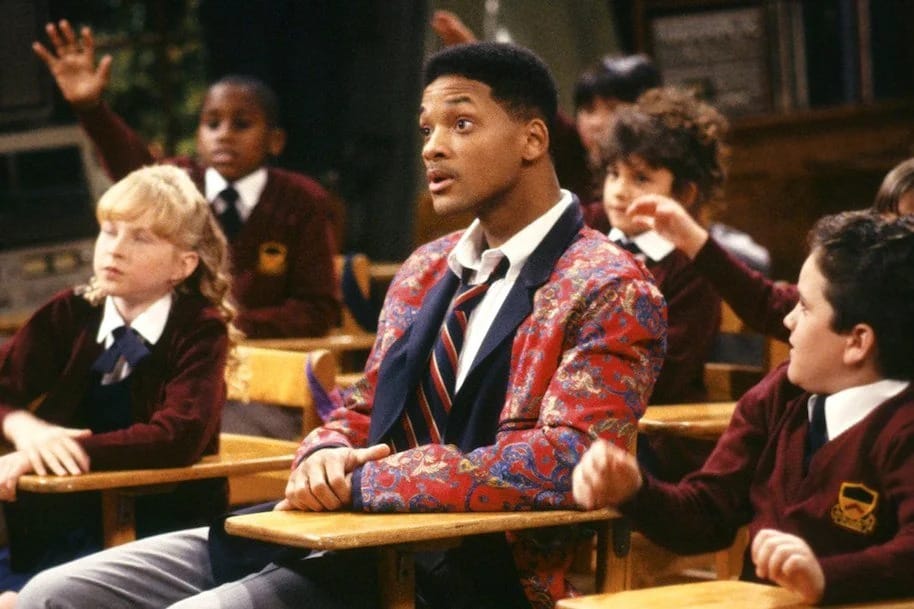

The Fresh Prince

It’s amazing how one opportunity can redefine your life. I was just a regular kid - playing sports, listening to whatever music was cool, and getting A’s and B’s at my local public school. Then, one summer, my mom heard that Colorado Academy - the best private school in the state - was planning to let a few Black kids in for the first time.

They weren’t legally segregated or anything (I’m not that old!) but let’s just say diversity wasn’t their strong suit. Up until then, the only minority student they had from 1st through 12th grade was a mixed girl.

Tuition was a mind-blowing $20,000 a year, completely out of reach for families like ours. But whoever got in would receive a full scholarship.

I still remember the test. It was harder than the SAT I’d take years later - probably harder than any test I’ve ever taken. I walked out of that room certain I’d failed, hoping I’d maybe managed to get 20% of the questions right. Somehow, they let me in anyway.

I lived in Aurora, Colorado. The school? It was practically on the doorstep of the mountains - 45 minutes to an hour away with no traffic. But there was always traffic and sometimes snow. Every single day. And I didn’t even get to go straight there. First, I had to catch the bus, which was 15 minutes from my house.

My mom drove me to the bus stop every morning, and in the evenings - actually, let’s call it night - my Aunt Mary would pick me up. During the school year, I never saw an ounce of sunshine at home. My days started before dawn and ended long after it.

Academy

The commute was nothing compared to what happened once I got to class. I sucked at every subject. How the hell was I one of the smartest kids at my old school - student council president, always on the honor roll - but now I felt dumber than dumb? Ds and Fs, over and over. No glimmer of hope.

But I kept trying because that’s just who I am. I wasn’t ashamed of my shortcomings; I had to go to school anyway, so I figured I might as well make the best of it.

The homework, though. Oh my god. It was relentless. I had at least two hours on the bus every day, but I couldn’t do homework there because motion sickness would make me puke. Sleeping on the bus wasn’t an option either - I’d just sit there, tired and stressed, watching the miserable commuters.

By the time I got home at night, sometimes not until 8 p.m., I’d dive straight into my homework. Best case scenario, I’d be done by 10. Most nights, I was up until midnight, sometimes 1 a.m. Watching TV, playing outside, talking on the phone - things kids did back then - weren’t an option.

And then, at 5 a.m., it all started again.

You’d think weekends would be a break, right? Wrong. My mom didn’t play that. “Get up and do your chores.” Every Sunday morning, we’d go to church, no exceptions. The only thing I stole time for was watching the Broncos every Sunday afternoon - but even then, I couldn’t fully enjoy it. You can guess why. Homework. Always homework.

There were bright spots in class, even when my grades didn’t reflect it. I was learning - really learning. Every lesson was interesting. The teachers were phenomenal, and their passion was contagious. It wasn’t just their teaching; it was the way they cared about every student, even the five that looked like me, also barely scraping by. That sense of care extended beyond the classroom. Everyone was kind - students, staff, even the groundskeepers and janitors.

In Spanish class, I learned more in a few weeks than I did in years afterward. We started with a children’s book. Duh, that’s so obvious how you should teach it. My teacher was gay - not that he ever said it outright, but we all knew. No one cared. At my old school, he wouldn’t have lasted a week without being clowned relentlessly. Come to think of it, my old school wouldn’t have hired a gay teacher in the first place.

In English class, we watched Roots. The whole thing. Sure, it was technically English class, but we ended up discussing history, law, geography - everything. For two weeks, I got the best African-American education I’ve ever had. And I went to a black college. The discussions we had in that classroom? I would kill for that kind of dialogue to be possible today.

Bel-Air

But don’t get the wrong idea - these weren’t liberal hippies. I went to school with the kids of Republican billionaires. John Elway’s kids. Pat Bowlen’s kids. Pete Coors' grandkids. Owners of the Broncos and beer company. That was the world I’d stepped into.

One Saturday, I went to a friend’s house. I was expecting the usual - maybe a nice house, but nothing extraordinary. Instead, I walked into a mansion. The first I’d ever seen. A pond in the entryway. Two staircases curving up like in the movies. His game room was better than the arcades where I used to pay quarters to play. His bedroom was better than my imagination. His playroom? Bigger than my whole house.

But the biggest lesson I learned about wealth wasn’t in those mansions. It was in the small details. The really rich kids? They didn’t act like it. They wore plain, often raggedy clothes. Their moms drove Volvos that were at least ten years old. Or maybe brand-new Volvos. Who could even tell? They never talked about money, never bragged, never showed off. They just lived. The rest of us were the ones pretending.

Meet Me at the Crossroads

I played lacrosse because, for the first time, I couldn’t play football - they didn’t have a team. I still played like it was football, though. A few kids learned that the hard way.

And then, something amazing happened. Without even realizing it, my grades started to improve. Ds and Fs turned into Cs, and eventually even a pity B - no, definitely not a pity B. They would never hand out grades you didn’t earn at Colorado Academy.

The school year flew by. Looking back, May always seems to sneak up on you, even though September feels like it drags forever. That summer, I finally got to be a normal kid again. I hung out with my old friends, and they missed me. I missed them, too.

And then my dad - well, my stepdad, whatever - brought up basketball. He pointed out that I was tall, good at the game, and always playing whenever I could. He said I should go to the local public school, where they had a better coach and better competition. I could play college basketball.

I don’t know if that’s exactly how it went, but I’m sure his intentions were good. Tell any boy they might make it in basketball, and their eyes light up. I probably should’ve told him - or my mom - that I was excited to go back to Colorado Academy. I wasn’t miserable there, even though I was exhausted all the time. I liked proving I wasn’t dumb. I wanted to get back to A’s and B’s, honor roll, student council president - everything I’d been before.

But I didn’t.